I have come to believe that it’s not the system, the approach, the instrument, the qualification or the content that defines what makes a good music teacher. It’s the difference between ‘doing D’ and ‘we don’t do D’.

As part of my training and development role with Musical Futures International, I was recently involved in leading workshops to support the implementation of a new curriculum for music. One session we were asked to deliver was approaches to teaching whole class ukulele – an instrument specified in the curriculum to be taught at upper primary level. The curriculum specifies that at this level (ages 9-11) that,

“Repertoire should be based on the following tonalities:

• C pentatonic mode

• C, F, G major and A minor.”

Note: I am deliberately not identifying the curriculum as I don’t want to be in any way critical of what is in it. What I am interested in is how literally it has been taken by teachers and that is why Musical Futures International was there – to start to challenge teacher mindsets, not about what is being taught but how and why through a series of intensive and practical CPD workshops for teachers.

Part way through the workshop we put up the uke chord D on the screen and my colleague Stephen asked the teachers whether they recognised it and could play it on their ukes.

Their reply, ” We don’t do D”.

Surprised, we asked why not. What do you do if a song has D in it? The answer – teachers transpose the songs into C and only use songs that have C, Am, F and G in them.

I wanted to ask whether they had thought about why their students are learning ukulele at all. Is the instrument just a tool through which students can tick the required boxes – I can play C, G, Am and F on the uke, I can almost play C, G Am, F on the uke, I aspire to playing C, G, Am and F on the uke etc etc….

It seemed a missed opportunity to give students whose only engagement with music might be in the classroom the incentive to go home, pick up a ukulele and play any song that they want to learn that isn’t in C.

Perhaps they might compose their own songs, using a range of chords other than C, Am, G and F to create a mood, a feel, a tonality that allows them to express themselves musically or to tell their own story.

Where is the stretch and challenge for students who can or want to play more than just those 4 chords, but might never get the opportunity to try or demonstrate this in class?

And a quiet voice in my head was wondering how quickly the students might get bored and disengage if all they were ‘allowed’ to play was C, Am, F and G…

The next day we taught a model lesson to a class of 40 upper primary students all of whom had their own ukulele. We used a current song, one that many of them knew and they immediately started to sing along as soon as we played them the track. It had D and Bm in it.

In 10m they were able to give a class performance. Some students just played one chord, some played two. Others played the full sequence of Em, C, D, Bm using a simplified one finger, one fret, 3 strings hack that we showed them to move from D to Bm. At first, they played along with the song so the track became their safety net. Those playing just one chord had a part which fitted within a wider musical context. All could assimilate and copy aspects of the musical style as they played along.

Everyone participated. Some sang as they played. Some embodied the pulse or mimicked the sounds in the music through movement. Some came to life where previously they hadn’t stood out in the warm ups and rhythm activities we started the lesson with. Most left the classroom humming the song. Some asked to take the resource (something I had just thrown together to use with my own classes) so they could practice.

It was raw and unfinished but it had an outcome that went from nothing to something. It was an experience for those students of an end point which then revealed possibilities for unpicking and rehearsing and improving and learning over subsequent lessons.

Our hosts were pleased to be able to video that lesson as an example to the teachers of how restricting the content or making assumptions about what students could or couldn’t do could lead to missed opportunities for valuable musical learning and participation.

My reflections

- Perhaps the limiting of the repertoire in the curriculum is there to get teachers across the starting line with instruments and approaches they probably haven’t experienced themselves. If that’s the case, then that’s a great start point. So if CPD like ours is pushing the teachers beyond those initial boundaries therein lies the key to bringing a curriculum document to life. Put it in the hands of teachers then offer regular CPD to make what is in it engaging, contemporary and relevant to their students. The best way to improve is to keep learning and developing as teachers and as musicians and it never stops. For as long as we are teaching, we are learning….

- Developing hacks that get all students playing first, engaging them with a real musical experience is important. Then diagnosing what they need to do it better, teaching through a range of approaches and strategies until defined musical objectives are reached, makes classroom music more democratic and keeps teachers searching for fresh approaches to keep classroom music musical

- I am worried about the continuing debates about one approach being better than another. The need to be trained in Kodaly, Orff, EYFS pedagogy etc to be able to successfully teach primary or EY music, questions about whether secondary trained music teachers are in fact qualified to teach primary or EY music, can generalist teachers ever successfully teach music – on and on and round and round it goes.

I am sensitive to the discussion as I am now teaching EY-Y9 music in an international school having spent 18 years teaching secondary music in the UK. I have also worked in teacher development, leading workshops with adults for the last 17 years. Some of these debates have led me to question whether I ‘should’ be doing these things. Am I sufficiently qualified to be teaching primary or EY music as my initial teaching qualification was secondary?

Perhaps if I considered that my development as an educator stopped when I got my QTS certificate then some of these accusations might have some merit. But in my experience visiting and teaching in classrooms across the world, some my own, others as a guest or an observer, I have come to believe firmly that it’s not the system, the approach, the instrument, the qualification or the content that defines what makes a good music teacher. It’s the difference between ‘doing D’ and ‘we don’t do D’.

I believe that teachers who ‘do D’

- are creative and confident enough to risk failing before they succeed

- find their way to CPD whether that’s attending in person or reading, learning, engaging in debates

- can build relationships with their students and their colleagues that allow for democratic learning to take place – learning can come from teacher to student and equally teachers can learn from and with their students

- recognise that there are many ways to learn and teach music and that being open to these is the first step in finding your own approach and voice

- have thought about what their students are learning, have asked why, and then considered how they will get there, in ways that allow for everyone to be a participant in their own musical journey

- create opportunities to tease out what their students can do rather than start with assumptions about what they can’t do

About Musical Futures International

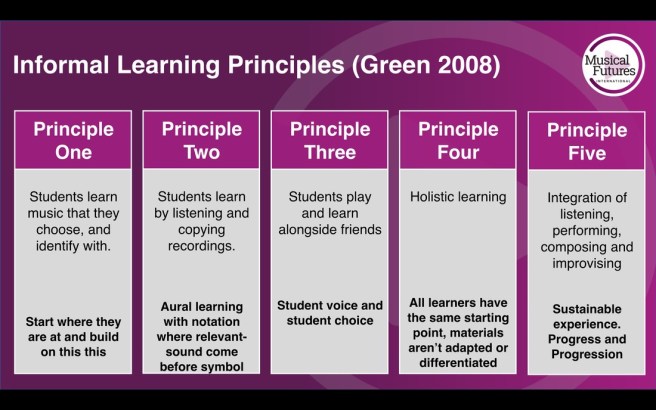

The Musical Futures International approach is to start with music that students recognise, like and engage with. It suggests using the music itself (rather than notation or theory) as the start point for learning. It advocates student choice where possible/appropriate and explores strategies for learning through large-group, small group and independent music making.

At our teacher development workshops we encourage teachers to look at alternative approaches to teaching music that might be different from the way they themselves learned.

We ask what happens if you start from the music rather than from notation or theory? If you can sing it can you play it? If you can hear it can you play it? If you can play it, can you better understand it and learn through and from being immersed in a musical experience? Can you become more musically creative if music itself becomes the tool for learning? is there value in making music together in groups, large and small as well as developing through personal practice that often takes place in isolation? This isn’t unique to Musical Futures by the way. There are overlaps and synergies with other approaches and we aren’t dogmatic about it. There are many ways to learn music…..